How would you like to achieve detailed exception and trace logging, including method timing and correlation all within a lightweight in-memory database that you can easily manage and query, as exhibited below?

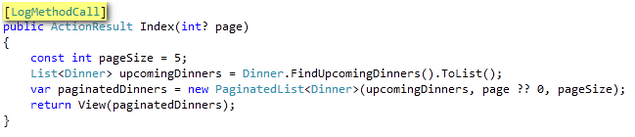

All of this requiring nothing more of you than simply decorating your methods with a very simple attribute, as highlighted below.

In this post, I’m going to demonstrate how to configure PostSharp, an aspect-oriented framework, along with NLog and SQLite to achieve the benefits highlighted above. Before I get into the details of the configuration and aspect source code, I’ll provide a bit of background on PostSharp.

PostSharp

PostSharp is a powerful framework that supports aspect-oriented programming using .NET attributes. Attributes have been around in the .NET Framework since version 1.0. If you weren’t used to using attributes in the past, their increased usage in WCF (including WCF RIA Services and Data Services), ASP.NET MVC, the Entity Framework, the Enterprise Library and most of Microsoft’s other application frameworks will surely mean you’ll be encountering them in the very near future. PostSharp allows you to create your own attributes to meet a variety of needs (cross-cutting concerns, in aspect-oriented parlance) you may have such as persistence, security, monitoring, multi-threading, and data binding.

PostSharp has recently moved from a freely available to a commercially supported product. PostSharp 1.5 is the last open source version of the product with PostSharp 2.0 being the first release of the commercially supported product. Don’t let the commercial product stigma scare you away, both PostSharp 1.5 and 2.0 are excellent products. If you chose to go with PostSharp 2.0 you can select either a pretty liberal community edition or more powerful yet reasonably priced Professional edition. For the purpose of this post, I’ll be using the community edition of PostSharp for forward compatibility. The Community Edition includes method, field, and property-level aspects, which is more than enough for the purposes of this post. You will also find examples of PostSharp aspects on their site, in the blogosphere, and on community projects such as PostSharp User Plug-ins.

What makes PostSharp stand out among competing aspect-oriented frameworks is how it creates the aspects. PostSharp uses a mechanism called compile-time IL weaving to apply aspects to your business code. What this essentially means is that, at build time, PostSharp opens up the .NET intermediate language binary where you’ve included an aspect and injects the IL specific to your aspect into the binary. I’ve illustrated below what this looks like when you use .NET Reflector to disassemble an assembly that’s been instrumented by PostSharp. The first image is before a PostSharp attribute is applied to the About() method on the controller. The second image represents what the code looks like after PostSharp compile-time weaving.

Before PostSharp Attribute Applied to About() Method

After PostSharp Attribute Applied to About() Method

What this means is that you get very good performance of aspects but will need to pay a higher price at build/compile time. Ayende provides a good overview of various AOP approaches, including the one that PostSharp uses. Don’t be concerned by his “hard to implement” comment. The hard part was done by the creators of PostSharp, who have made it easy for you.

Implementation of Aspect-Oriented Instrumentation

The remainder of this post will focus on the actual implementation of the solution. Much of the code I have here was cobbled together from a blog post I archived long ago from an unknown author. I’d love to provide attribution but, like many blogs out there, it seemed to have disappeared over time. I’ll start off first with the SQLite table structure, which can be found below.

The logging configuration file is very similar to my post on logging with SQLite and NLog with minor changes to the SQLite provider version.

The most important component of the solution is the source code for the PostSharp aspect. Before letting you loose, I’ve highlighted some of the features of the source code to avoid cluttering it with comments:

- You need to have PostSharp (the DLLs and the necessary build/compilation configuration) set up on your machine for the aspects to work correctly. Specifically, my code works against PostSharp 2.0

- For those of you not familiar with Log4Net or the original implementations of the NDC (NestedDiagnosticContext) and MDC (MappedDiagnosticContext), the original documentation from the Log4J project provides good background.

- The NDC is used to push GUID’s on the stack which can then be used as correlation ID’s to trace calls through the stack for methods annotated with the [LogMethodCall] attribute that this code implements.

- The MDC map stores timing information in all cases and exception information in the case of an Exception in one of the calling methods annotated with the [LogMethodCall] attribute.

- To use the attribute, just decorate the method you wish to instrument with the [LogMethodCall] attribute. Then sit back and enjoy detailed instrumentation for free.

using System;

using System.Diagnostics;

using NLog;

using NLog.Targets;

using PostSharp;

using PostSharp.Aspects;

namespace MvcApp.Web.Aspects

{

[Serializable]

public class LogMethodCallAttribute : MethodInterceptionAspect

{

public override void OnInvoke(MethodInterceptionArgs eventArgs){

var methodName = eventArgs.Method.Name.Replace("~", String.Empty);

var className = eventArgs.Method.DeclaringType.ToString();

className = className.Substring(className.LastIndexOf(".")+1, (className.Length - className.LastIndexOf(".")-1));

var log = LogManager.GetCurrentClassLogger();

var stopWatch = new Stopwatch();

var contextId = Guid.NewGuid().ToString();

NLog.NDC.Push(contextId);

log.Info("{0}() called", methodName);

stopWatch.Start();

NLog.NDC.Pop();

try

{

eventArgs.Proceed();

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

var innermostException = GetInnermostException(ex);

MDC.Set("exception", innermostException.ToString().Substring(0, Math.Min(innermostException.ToString().Length, 2000)));

log.Error("{0}() failed with error: {1}", methodName, innermostException.Message);

MDC.Remove("exception");

throw innermostException;

}

NLog.NDC.Push(contextId);

stopWatch.Stop();

NLog. MDC.Set("DurationInMs", stopWatch.ElapsedMilliseconds.ToString());

log.Info("{0}() completed", methodName);

NLog.MDC.Remove("DurationInMs");

stopWatch = null;

NLog.NDC.Pop();

}

private static Exception GetInnermostException(Exception ex)

{

var exception = ex;

while (null != exception.InnerException)

{

exception = exception.InnerException;

}

return exception;

}

}

}